As the New York metropolitan region faces the daunting prospect of a sea level rise of 6 feet near 2100, experts convened at the Urban Land Institute (ULI) Spring Meeting to discuss the challenges and opportunities ahead.

William Kenworthey, AIA, LEED AP, regional leader of urban design for HOK in New York, was a key voice on an April 9 ULI panel titled “NYC 2100: Resiliency, Housing and Equity for the Metropolitan Region with Six Feet of Sea Level Rise.” The panel brought together thought leaders in climate science, urban planning, public policy and design.

Dr. Christian Braneon, research scientist at the CUNY Institute for Demographic Research and co-director of the Environmental Justice and Climate Just Cities Network at Columbia Climate School, moderated the panel. He emphasized the importance of the discussion, noting that “sea level rise is coming.” Braneon added, “This is at the root of the climate justice question we’re facing today. Are we going to make decisions that make our children or our children’s children live in a world that’s uninhabitable in some ways?”

Braneon further stressed the need to protect the most vulnerable members of society, stating, “This session is really important because as we think about coastal flooding, and sea level rise, and the other effects that come from sea level rise, we should be thinking about how to protect the most vulnerable in our society. How do we protect the folks that often have contributed the least toward sea level rise but will bear the brunt of its effects?”

Dr. Bernice Rosenzweig, Osilas endowed professor in Environmental Studies at Sarah Lawrence College, provided context on the multifaceted flood risks beyond coastal storm surges. “It’s really important to keep in mind that New York City faces many different types of flood hazards,” she explained. “So, of course, we want to think about coastal flooding when we’re thinking about the impacts of sea level rise. But we have to think about how coastal flooding will interplay with other types of flooding that are going to be increased due to climate change.”

Robert Freudenberg, vice president of energy + environment at the Regional Plan Association, discussed the challenges of “managed retreat.” He noted, “The idea of moving away from where you are to somewhere else is really challenging. Then there’s the community that you live in. … We all live in a community for the reasons we live in it. It has the things we want, the amenities, our home is there, the people that we are friends with and work with, and all the services it provides. It’s a tremendous loss to consider moving away from that community.”

Michael Marrella, director of climate and sustainability planning at the New York City Department of City Planning, outlined the city’s resiliency initiatives and the importance of considering social vulnerability. “The truth is that so much of the funding that is right now being used for coastal protection projects is tied to Sandy recovery,” he explained. “What we have ahead of us, though, is an important reset in some ways of determining where we need to be spending our next dollar. And the scale of coastal protection projects almost certainly leads to federal funding.”

Kenworthey shared insights from HOK’s NYC 2100 research project, drawing on his experience with former Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s Superstorm Sandy recovery efforts. “Having worked on Sandy recovery efforts published in a comprehensive plan called, ‘A Stronger, More Resilient New York,’ and looking at 30 inches of sea level rise, we understood what certain neighborhoods might have to do to protect themselves with infrastructure,” he said.

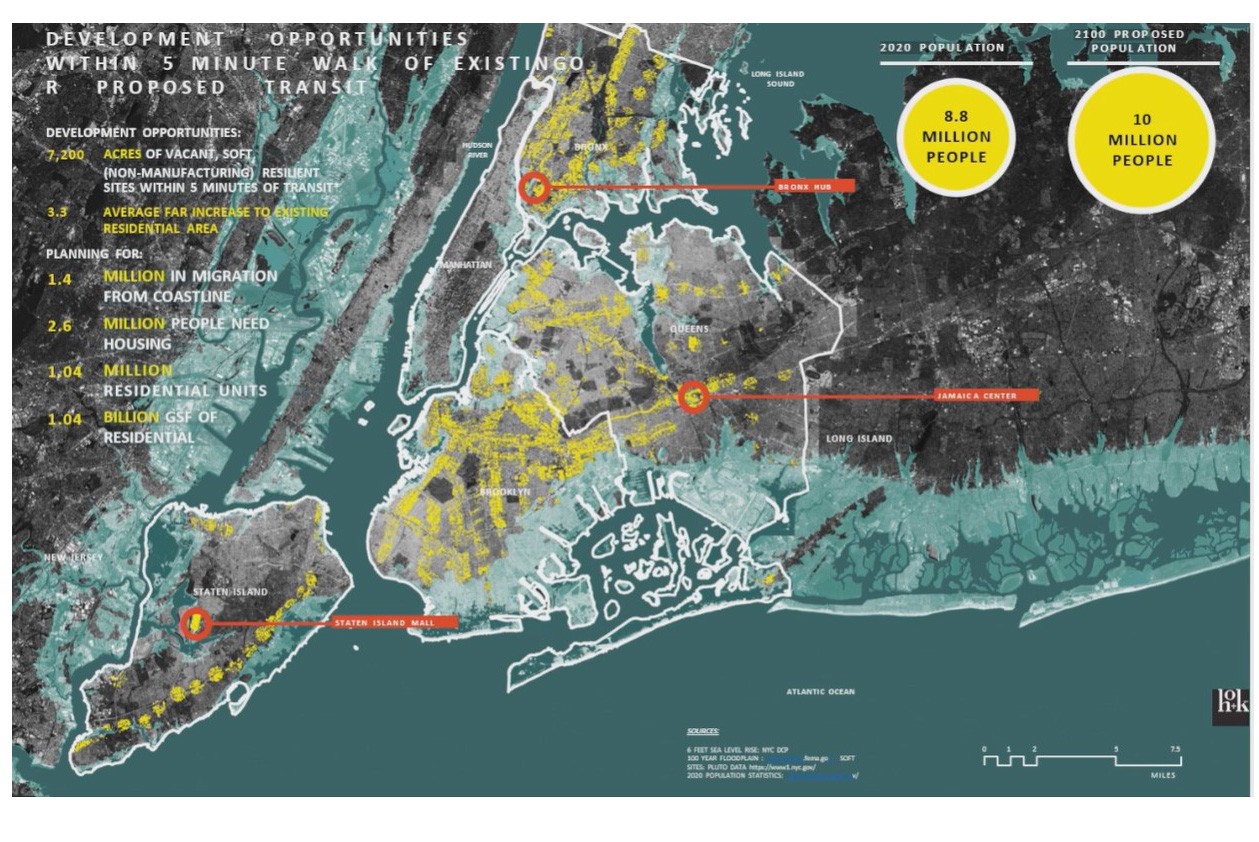

Under a 6-foot sea level rise scenario, Kenworthey described a dire situation in which more than 60,000 acres, home to 1.4 million New Yorkers, would be in the 100-year floodplain. He emphasized the disproportionate impact on vulnerable communities, particularly in Queens, the Bronx and Brooklyn, where predominantly Black and Brown populations and 155,000 households living under the poverty line would be at risk. The potential damage to critical infrastructure was also severe, with Kenworthey pointing to 4,000 industrial lots, 332 healthcare facilities, 20,000 acres of parks and 18 power plants facing the threat of flooding.

However, Kenworthey highlighted a potential solution identified by HOK’s analysis. Nearly 7,200 acres of underdeveloped or vacant land under today’s zoning located within a 5-minute walk of existing or planned transit are “high and dry,” meaning they would remain safe from flooding even with 6 feet of sea level rise. These areas could accommodate over 1 million new residents with strategic upzonings for mixed-use development. Kenworthey emphasized the importance of considering these opportunities for growth and development as the city may reach a population of 10 million by the end of the century, allowing New York to continue growing despite the risks posed by climate change.

However, Kenworthey highlighted a potential solution identified by HOK’s analysis. Nearly 7,200 acres of underdeveloped or vacant land under today’s zoning located within a 5-minute walk of existing or planned transit are “high and dry,” meaning they would remain safe from flooding even with 6 feet of sea level rise. These areas could accommodate over 1 million new residents with strategic upzonings for mixed-use development. Kenworthey emphasized the importance of considering these opportunities for growth and development as the city may reach a population of 10 million by the end of the century, allowing New York to continue growing despite the risks posed by climate change.

Kenworthey walked the audience through visualizations of how neighborhoods could be reimagined, with former industrial waterfronts becoming floodable parks protecting new mixed-use developments and low-rise streets transforming into mid-rise affordable housing corridors centered around new approaches to streetscape and mobility. He emphasized the need for bold, long-term thinking and proactive, inclusive planning to protect marginalized populations.

The discussion provided a preview of the planning challenges ahead, while spotlighting the interdisciplinary work needed to equitably adapt New York and other coastal cities to an uncertain climate future. Having these difficult public conversations now will allow regions like New York to begin steering policy and development in a more sustainable, equitable direction.