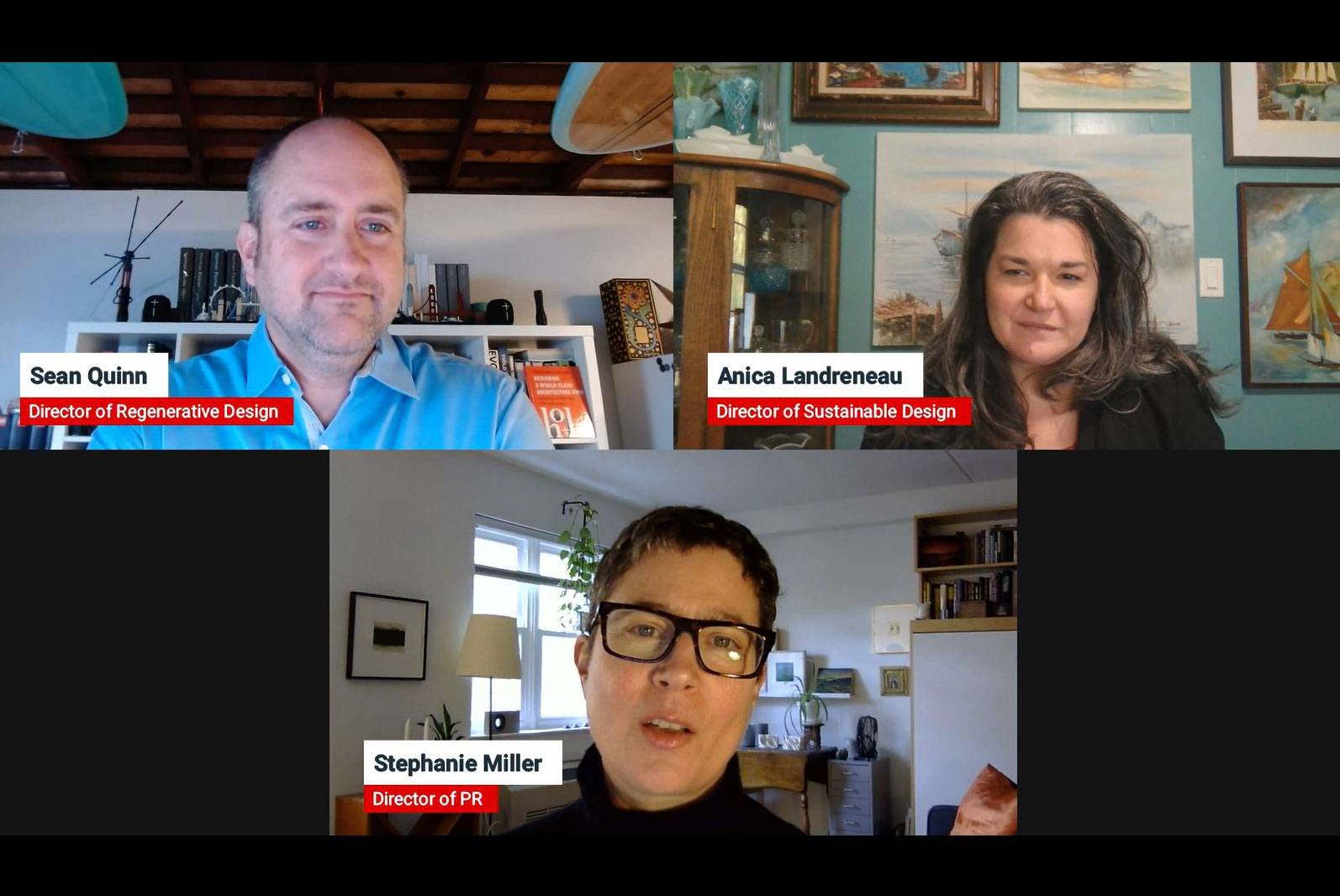

In advance of this year’s UN Climate Conference, HOK’s Director of Sustainable Design Anica Landreneau and Director of Regenerative Design Sean Quinn discuss the issues COP28 delegates need to address to improve the built environment and safeguard the planet.

The building sector plays an outsize role in contributing to climate change. According to the UN’s latest data, emissions from building construction and operations (such as heating and cooling) accounted for more than one-third (37%) of global carbon emissions in 2021. With so much at stake—and so much room for improvement—HOK hosted a LinkedIn Live to examine the sustainability and resiliency issues COP28 delegates need to pursue when it comes to architecture, planning and the built environment.

Watch the entire panel conversation below, or jump down to the 5 biggest issues we hope to see addressed at COP28.

1. Standardize Codes and Toolkits

As it stands now, countries aren’t always speaking the same language when it comes to sustainability and resiliency within the built environment. To remedy this, Landreneau discussed the need for nations to create standardized building and energy codes and common definitions for terms such as zero emission and near-zero emission buildings.

“Building codes are a great place to start, but we also need to realize we are not going to build our way out of climate change,” said Landreneau. “We must address our existing building stock. I hope to see a broader discussion around a building policy toolkit—something that addresses both new and existing buildings and builds consensus around tools all countries can use to address emissions as they relate to the built environment.”

2. Rethink Resiliency

Resiliency, too, can have many different definitions. Quinn and Landreneau both discussed the need to reframe the current attitude about resiliency. Instead of viewing nature as the enemy, countries should leverage nature to help blunt the effects of climate change.

“We’ve been innovating in gray infrastructure for the past century,” said Quinn. “Going forward, we need to be thinking about more green infrastructure solutions and increasing our intelligence around civil engineering” by integrating more living and natural infrastructure into communities.

Landreneau highlighted the use of nature to mitigate climate change and make communities healthier and more resilient.

“We need to look at ways of investing in deep green, carbon-sequestering landscapes such as forests, parks, wetlands, mangroves, bioswales, shorelines and riverbanks,” said Landreneau. “There are co-benefits to that carbon sequestration and regreening. It provides greater biodiversity, cleaner air and water, and provides heat island mitigation in cities.”

3. Address Embodied Carbon

The energy used to create and transport building materials is another significant source of greenhouse gas, contributing to up to 11% of global emissions. New measures are needed to track building performance and spur innovation, which will help lower the embodied carbon tied to materials and construction.

Quinn suggested that COP28 delegates look to California, where a new state mandate requires large-scale construction projects to track and mitigate embodied carbon. He also encouraged the private sector to pitch in by developing technologies that reduce embodied carbon in building materials. Examples include low-carbon cement, which reduces the notorious levels of emissions required to create concrete, and new biological systems that can grow bricks and other building materials.

“Investing in these types of solutions, evaluating them, and bringing them to scale will provide the roadmap for how we get to carbon neutral structures—or even carbon sequestering structures,” said Quinn.

4. Jumpstart Green Financing and Incentives

Money will be a major topic at this year’s COP, with delegates expected to advance calls for an international loss and damage fund. Such a fund would require wealthier, higher-emitting nations to pay into a pool to assist developing countries disproportionately affected by drought, floods and rising sea levels related to climate change.

But getting nearly 200 stakeholders to agree on the parameters of a loss and damage fund will require complex negotiations. Landreneau is more optimistic about individual countries—and their regulatory bodies—taking action to curb emissions and invest in resiliency.

“In the U.S., incentive packages like the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act have moved mountains of money to jumpstart green development,” noted Landreneau. “We also need financial institutions and the private sector to leverage financing solutions. We’re starting to see some of that with proposed SEC rule changes and the EU’s Taxonomy Regulation that require public companies to publish climate disclosures.”

Quinn pointed out that investing in climate change can seem costly now, but its return on investment dwarfs its initial costs.

“Spending $1 billion on resiliency today can save $5 billion in recovery costs tomorrow,” noted Quinn. “But we do need to be more creative about how we’re investing that money. It can’t simply be towards reinforcing seawalls. It needs to also enable the mitigation of the systemic events generated by climate change.”

5. Quit Stalling

A report released this month revealed that Earth’s temperature is warming far faster than the 1.5-degree Celsius goal adopted during the 2015 UN climate summit in Paris. Temperatures are now expected to rise 2.5-2.9 degrees Celsius (4.5 to 5.2 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial times unless global emissions are cut by 42% by 2030.

Such temperature rise not only impacts future plant and animal life, but also directly threatens the resiliency of communities. Already, major insurers are exiting or limiting coverage in regions of the world most impacted by change. Without insurance, homeowners and developers can’t secure financing for new construction. They also face the increasing likelihood of having to pay out of pocket to repair and replace properties damaged by extreme weather. This is especially true as FEMA and other taxpayer-supported disaster funds struggle to keep up with an influx of claims associated with climate change.

In short, it’s beyond urgent that nations reduce carbon emissions now, and there’s no better place to start than with the elephant in the room, a.k.a., buildings and construction.

“Whether it’s decarbonization, resiliency or more equitable development, every nation participating in this year’s COP needs to model best behavior,” said Landreneau. “They need to innovate, take risks and model solutions that people in the public and private sectors can follow.”