Chris DeVolder, AIA, LEED AP, WELL AP, wants sports facilities to generate resources for their communities.

As the sustainable design leader for HOK’s Sports + Recreation + Entertainment practice and co-chair of both the Green Sports Alliance Corporate Membership Network Steering Committee and the USGBC’s LEED User Group for sports venues, DeVolder has helped reinvent the industry’s approach to the planning, design, construction and operations of sports venues. The managing principal of HOK’s Kansas City office shares his ideas about designing these community pillars for sustainability and resilience.

I have drums to thank for the direction of my career. Twenty years ago I was playing drums in a band made up of Kansas City architects. The lead singer was passionate about sustainability and was working on a sustainably designed residence for a client in his free time. He asked if I’d be interested in helping with his project. That moment changed my career. He gave me a copy of “The Sacred Balance” by David Suzuki that, coupled with his mentorship, fueled my passion for sustainable design.

Three things were happening when sustainability made a splash on the sports scene. First, jurisdictions and campuses had begun to require LEED certification for new buildings. Second, there was an influx of organic, student-driven movements around campus recycling that athletic departments were supporting. Third, operators of these massive sports facilities began to look at their rising water and energy consumption and felt motivated to change.

About this time the Green Sports Alliance was founded. At the organization’s first conference in 2010, most presentations were case studies of buildings that had upgraded their water and energy efficiency. We’ve come a long way.

Today’s proactive owners and operators are seeking innovative strategies around community, food and renewable energy. Sustainability was once a completely cost-driven decision for owners and operators. Now there’s also a moral component. Our clients have a better understanding of opportunities to use these facilities to support campuses, neighborhoods and cities.

Our stadiums, ballparks and arenas are highly visible buildings that are accessible to the entire community. They provide an incredible opportunity to teach people about sustainable design. The first thing many of us do every morning is check sports headlines and scores. With our unwavering loyalty to teams and universities, sports has a unique platform to communicate sustainability and change behavior.

We encourage clients to think about sustainability as it relates to design, operations and messaging. There are so many potential touchpoints in a one million-square-foot building. Our clients can use their new canvas to communicate messages about energy efficiency, water conservation, recycling and more. I always laugh thinking about the signs in the bathrooms at Lincoln Financial Field in Philadelphia telling fans to “recycle beer here.”

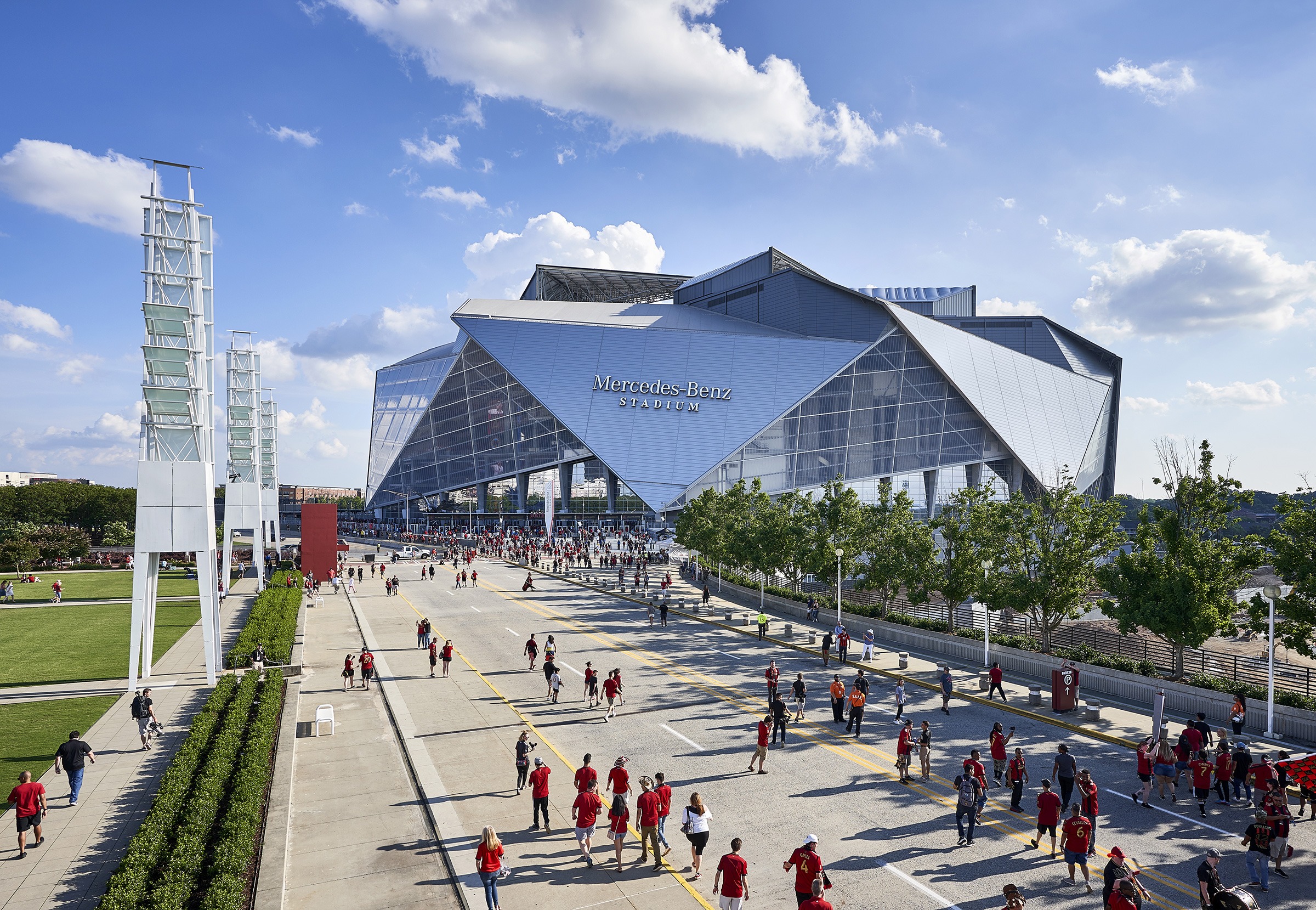

We embolden clients to find strategic partnerships that support their broader sustainability goals. For example, Mercedes-Benz Stadium, which achieved LEED Platinum, partnered with Georgia Power to integrate more than 4,000 solar PV panels. Every year they generate enough energy to power nine Atlanta Falcons games and 13 Atlanta United matches.

Sports architects have a responsibility to design sustainably, even if it isn’t a client-mandated goal. These are significant investments for owners and communities. We’re obligated to design buildings that are more than just a wonderful place to watch a game. They should be cornerstones of communities, generating resources and contributing to the greater good.

As part of their facility planning process, our clients develop profit and loss documents that outline the costs of running their venue. This is a critical time for us to advocate for sustainable design. As we help them understand the realities involved with operating a building of this scale, we explain how sustainable strategies like daylighting, LED lighting, water-efficient fixtures and equipment, and use of healthy materials can mitigate their costs. Aside from salaries, utilities often are the second-highest expense for a sports facility. So they are motivated to listen.

Resiliency is the only option. Many of these buildings can hold more than 60,000 people and simply can’t afford to lose power as we saw with Super Bowl XLVII in New Orleans. At the least every building needs redundant power.

When I consider how we address and plan for catastrophes, I think back to 2005 and Hurricane Katrina. If the Superdome had been designed for resiliency, it could have acted as a community shelter. Sports venues should be places of refuge during catastrophes and, ideally, incorporate basic healthcare components. These healthcare clinics or outposts could be accessible year-round while playing important roles during emergencies. The University of Washington’s Husky Stadium in Seattle, for example, has a rehab clinic that seemingly could aid the community in times of need.

When it comes to what’s next in resiliency in sports, facilities are moving from a scarcity mindset to one of abundance. Our projects shouldn’t just be about reducing water and energy use. They should capture and reuse water and generate renewable energy. These self-sufficient buildings won’t be dependent on utilities in an emergency. Add a kitchen and self-sufficient food storage to the site and the venue will be able to serve the community for days.

We expect to see an increased focus on the health and wellness of a facility’s users. In the past, designers were focused on the buildings themselves. Now we’re thinking more about the people who occupy these buildings. A healthy building promotes healthy bodies.