Imagine receiving a letter from your home insurer explaining they’re leaving your neighborhood entirely due to rising climate risks. This scenario isn’t hypothetical. Insurers are increasingly pulling back from high-risk coastal markets as climate threats escalate, leaving homeowners with fewer coverage options and higher premiums. The private market sees what’s coming, ready or not.

With nearly one-third of the population of New York City’s Queens Community District 10 (a low-lying area including Howard Beach, Hamilton Beach and parts of Ozone Park) projected to face regular flooding by 2100, the urgency behind Queens 2100 is clear. The research provides concrete recommendations for addressing climate threats in this vulnerable low-lying area.

From Citywide Vision to Neighborhood Action

HOK’s earlier NYC 2100 study imagined a future New York reshaped by six feet of sea-level rise. It raised urgent questions: Where will people go when their homes are underwater? And how can urban planning protect vulnerable communities?

Queens 2100 picks up where the citywide vision left off, zooming into a single neighborhood to explore what real adaptation might look like on the ground. To turn vision into actionable steps, HOK partnered with HR&A Advisors, an economic development and public policy consulting firm.

“Effective strategies must be technically sound and financially viable for residents and investors,” says William Kenworthey, AIA, HOK’s planning leader in New York and co-author of Queens 2100, “HR&A provided this essential real estate lens.”

The team selected Queens Community District 10 as a pilot area based on the following:

- Severe flood risk, with substantial inundation projected as early as 2050

- High proportion of homeowners in one- to four-family homes, with generational wealth at stake

- Strong local interest in addressing climate threats

Kenworthey puts the challenge bluntly: “This isn’t about if the water is coming. It’s about how soon and how prepared we’ll be when it does.” Queens 2100 lays out escalating risks across three timelines:

- 2050: Approximately 30 inches of sea-level rise; increased rainfall causes stormwater backflows into streets and basements.

- 2080: About 58 inches of sea-level rise routinely floods major roads and critical infrastructure.

- 2100: Over six feet of sea-level rise inundates entire neighborhoods, threatening homes, roads and vital services.

The Human Stakes Behind the Data

Flooding poses a direct threat to thousands of New Yorkers in Community District 10—endangering more than 1,600 jobs, 4,700 homes and over 200 local businesses. Lower-income households, communities of color and older adults face the greatest risk, making climate adaptation an environmental justice issue.

Homeowners are the backbone of these neighborhoods. For many middle-income families, home equity is their primary source of generational wealth. Flooding jeopardizes that asset by lowering property values and inflating insurance costs.

“Homeownership has become out of reach for most New Yorkers—but in these neighborhoods, many working-class families have still managed to achieve it,” says Jon Haragold, co-author of the study and a principal at HR&A. “Now, the growing threat of flooding puts both their homes and their generational financial security at risk.”

Renters, while more mobile, absorb costs indirectly as landlords pass along higher premiums and maintenance expenses in the form of rent increases. Local businesses face disruptions to their operations, lost revenue and damaged inventory. These economic impacts ripple through entire communities.

Having mapped the risks, Queens 2100 then identifies five practical tools neighborhoods can use to shift growth away from flood risks toward transit-rich areas.

- Flood-Risk Disclosure Laws: Require sellers within FEMA flood zones or projected sea-level-rise areas to disclose risks, ensuring informed property transactions.

- Buyouts and Relocation: State or federal programs purchase high-risk properties, remove development rights and convert land to permanent open space. These buyouts reduce exposure and taxpayer burden.

- Life-Cycle Leasebacks: Owners sell properties (often to a public entity) but lease back temporarily, providing immediate financial relief and predictable relocation timelines.

- Transfer of Development Rights (TDR): Moves development potential from vulnerable sites to higher-ground areas, compensating property owners and preventing risky intensification.

- Resilience-Focused Rezoning: Updates zoning to direct growth incentives to safer areas, restricting new investment in vulnerable flood zones.

From Strategic Growth to Action: A Playbook Beyond Queens

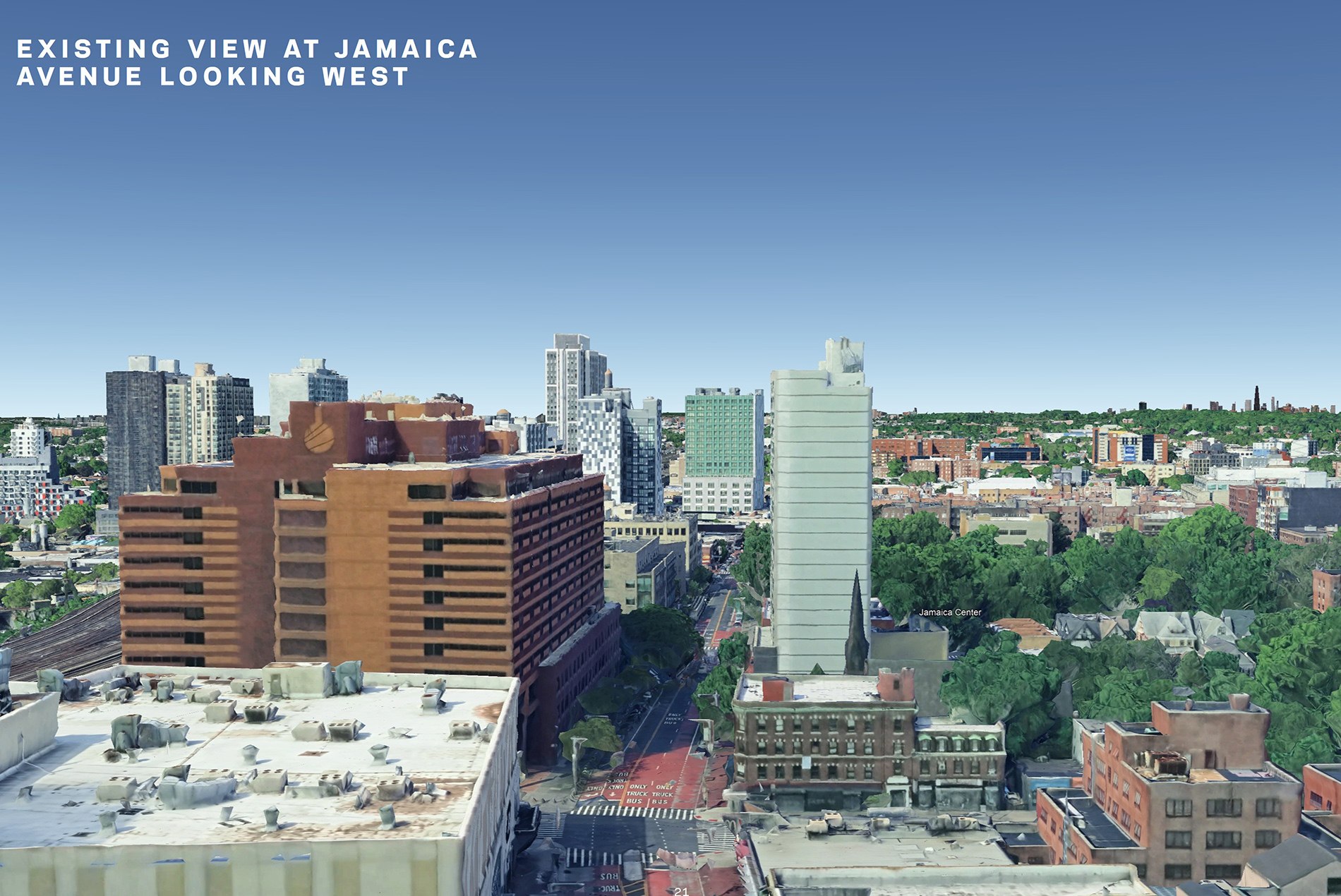

Queens 2100 targets Jamaica Center and corridors like Jamaica Avenue for transit-oriented redevelopment. These areas can absorb more affordable housing, mixed-use buildings and local retail—concentrating growth where infrastructure already exists.

This strategy is more than a study. It’s a call to act before crisis hits. Early dialogue among homeowners, planners, businesses and officials is essential. The toolkit offers communities practical, voluntary pathways to maintain agency, dignity and stability as flood risks evolve, shaped by ongoing local input.

Nearly 40% of Americans live in coastal counties facing similar climate threats. Queens 2100 offers cities a flexible, scalable framework:

- Policymakers: Pass disclosure laws and enable TDR and leaseback programs.

- Investors and insurers: Align capital protection with equitable resilience strategies.

- Residents: Start informed conversations about protecting homes, livelihoods and generational wealth.

Incremental, proactive steps today can transform climate threats into manageable transitions—one neighborhood and one coastline at a time.

To Learn More

Queens 2100 is intended to start conversations. The full presentation catalogs over one thousand small-scale green-infrastructure projects already underway in District 10. It also maps critical public services—police and fire stations, schools and clinics—against 2050, 2080 and 2100 flood-risk scenarios. By highlighting both existing adaptation efforts alongside critical gaps, the study gives community leaders and policymakers a clear sense of where further investment and planning are most urgent.

Those at organizations, agencies or communities exploring similar climate-resilience challenges are encouraged to contact the study’s authors:

William Kenworthey – Principal and Regional Leader of Planning, HOK, New York (william.kenworthey@hok.com)

Jon Haragold – Principal, HR&A Advisors, New York (jharagold@hraadvisors.com)

Image credits:

- Image 1 – Flood risk map of NYC boroughs: Map by HOK

- Image 2 – Flooded street with storefronts: Photo by Pamela Andrade, licensed under CC BY 2.0, via Flickr

- Image 3 – Aerial view of Queens residential neighborhood: Photo by Tdorante10, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Image 4 – Waterfront houses and boats along canal: Photo by David Shankbone, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Image 5 – Aerial view of Jamaica Avenue looking west: Google Earth satellite imagery

- Image 6 – Architectural rendering of proposed Queens street design: Rendering by HOK

- Image 7 – Howard Beach wetlands panoramic view: Photo by Андрей Бобровский, licensed under CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons