Kristine Bishop Johnson, director of HOK’s Justice practice, shares design strategies for future-proofing courthouses with a focus on flexibility, technology, security, well-being and equity.

Built in 1725, King William County Courthouse in rural Virginia opens once a month for civil hearings and—more importantly—to maintain its distinction as the nation’s oldest courthouse in continuous operation. At nearly 300 years old, the one-story brick building is a stunning example of pre-Revolutionary War architecture. Yet for today’s purposes, King William County doesn’t measure up.

With just one courtroom, the building is too small to handle the county’s current caseloads, nor can it accommodate the security, technology and accessibility requirements required of modern courthouses. In these limitations, King William County is hardly alone.

Across the nation, hundreds of state, federal and municipal courthouses face similar challenges. Designed and built for another era, they lack separate and secure circulation paths. Their technology infrastructure cannot support today’s hybrid proceedings. Aesthetically and functionally, they fail to provide a healthy and inspiring environment for visitors and employees.

So, how can governments and courthouse planners design buildings that will remain relevant and useful well into the future? They can begin by paying attention to the following five themes.

1. Design for Flexibility

A new courthouse can be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for a community. A facility designed and built today must be able to adapt to future uses and possible expansions. Planning to accommodate flexibility over the life of the building should be addressed as early as the programming phase.

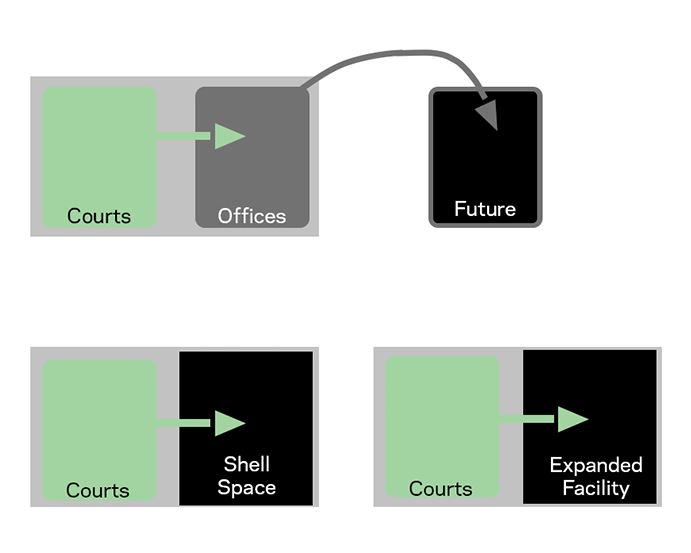

The best ways to provide future flexibility are by creating opportunities for horizontal or vertical expansion of the building.

Horizontal expansion: Adding programmatic functions outside an existing envelope is often easier to accommodate and can be less disruptive to ongoing court operations. This is only possible, however, if the site is large enough to allow for external expansion.

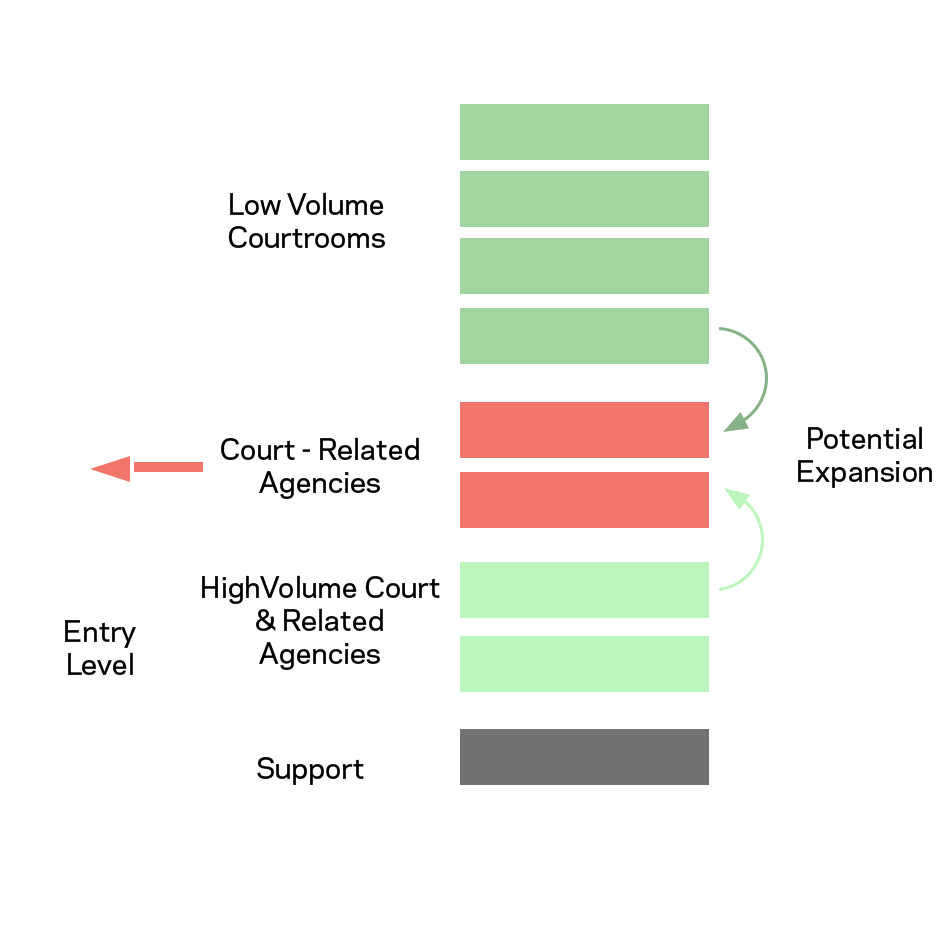

Vertical expansion: Planners can achieve flexibility within an existing building by stacking courtrooms and departmental functions to allow them to adapt for new uses. Courtrooms, for example, can be efficiently stacked and, if need be, easily segmented in the future for new, alternative functions, such as hearing rooms, departmental space or other amenities. Vertical expansion also can be accommodated with shell floors that can be fit-out to suit future needs.

Employing space standards that reinforce the modularity of spaces as well as incorporating uniform floor-to-floor heights throughout the building are good practices that will make future space conversions feasible.

As technology plays a larger role in judicial transactions, courtrooms and support spaces, such as record rooms, should be designed to adapt for new uses and demands. Records spaces or libraries, for example, could be located in sections of the building that would allow for their transformation into additional office, courtroom or meeting space.

2. Design for Technology

New technology, such as video conferencing, e-filing and online jury screening, has made accessing the courts easier and sometimes reduced the need for in-person visits. At the same time, not all people have access to technology, and courthouses must continue to provide in-person services to these constituents.

Technology infrastructure must be a key part of courthouse planning. It should be robust enough to accommodate ever-growing data demands and readily accessible, allowing for easy system upgrades and plenty of access points for plugging in and connecting devices.

Technology integration must emphasize equity. People interacting virtually with the court should be able to do so in a way that does not impact their ability to participate effectively. They must be able to be seen and heard and to seamlessly follow courtroom proceedings.

Those with limited access to or knowledge of technology should also be provided space within the courthouse to interact electronically. This could be through kiosks in the building or dedicated technology rooms where self-represented litigants and others can participate in hearings and access online court files and other resources independently or with assistance from court staff.

3. Design for Safety + Security

Safety and security are paramount in courthouse planning. Circulation paths are a critical component of courthouse security and operations. Screening upon building entry is now a routine part of any courthouse visit. But security shouldn’t begin and end at the front door.

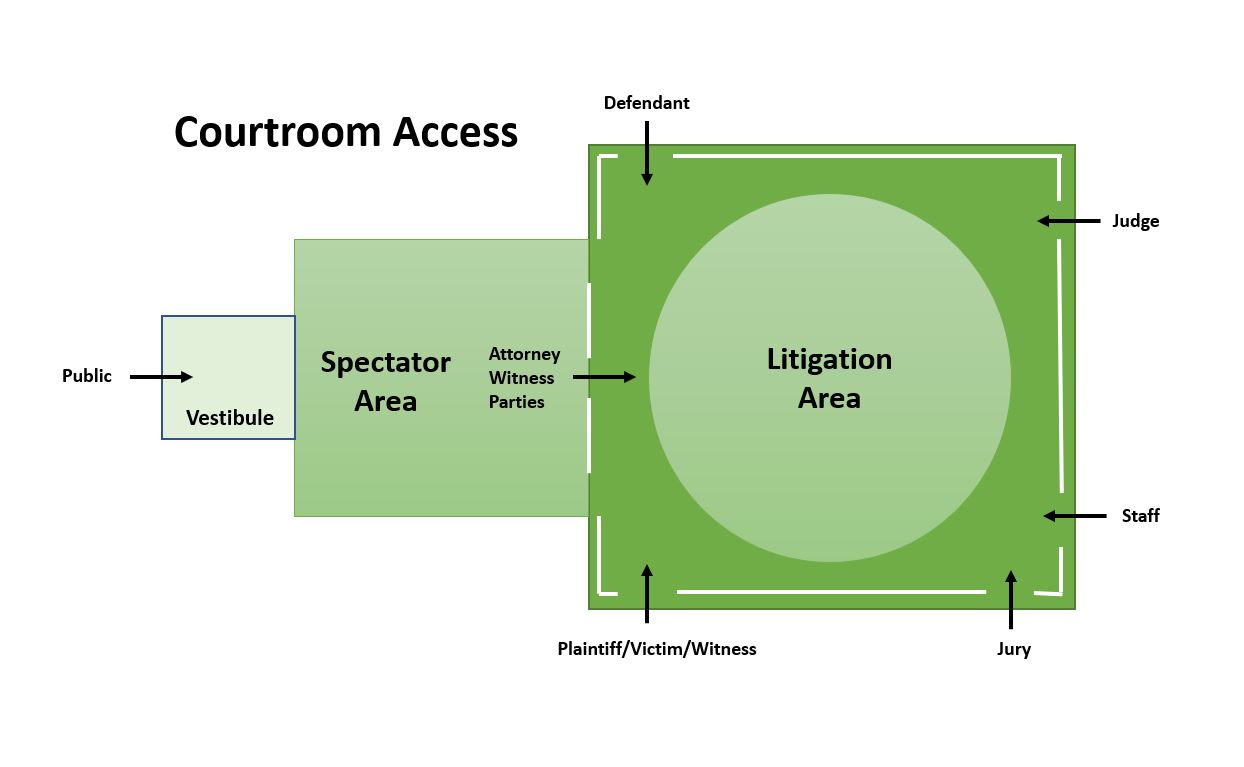

To ensure safety and impartiality, planners should consider how to design separate circulation pathways for judicial staff, in-custody defendants and the general public so the only point of intersection occurs within the courtroom.

In response to ever-increasing safety threats, planners must seamlessly layer safety throughout the interior and exterior of the courthouse. A layered approach can start at the property perimeter by incorporating passive security elements throughout the landscape, such as planter walls and berms. These natural elements also help the courthouse appear more open and welcoming.

On the interior, clear sightlines and intuitive wayfinding make courthouses easier for visitors to navigate and help security personnel and first responders assess risks and quickly quell threats.

Technology will continue to play an expanding role in courthouse security in the decades to come. Electronic security and monitoring must be seamlessly integrated throughout the design of the building in a way that is unobtrusive while also making it clear that the court is under surveillance. Electronic security should augment—but not replace—sound planning practices.

4. Design for Health + Well-Being

Courthouses of the past often were designed to be more like fortresses than open civic spaces. While such architecture can instill a sense of authority and the rule of law, it isn’t particularly inviting or hospitable for visitors or employees. To continue to attract and retain talent and adapt to new expectations, the courthouse of the future should be designed with an emphasis on health and wellness and must incorporate trauma-informed design practices.

Courthouse planners need to be mindful of the anxiety and fear often associated with the legal process. Intuitive wayfinding, natural light, views of nature, access to choice in waiting areas and vertical accessibility, such as the ability to ascend an open staircase versus ride in an elevator, are all elements that can mitigate anxiety and support a healthier environment. Natural light and views to the outdoors, for example, have been shown to have a calming and healing effect on people. This biophilic (nature-based) design also improves employee productivity and well-being by helping people feel refreshed and awake.

Courthouses may also consider borrowing wellness strategies already used in corporate and commercial workplaces. These include offering employees a choice of work settings based on the task at hand, such as quiet heads-down workstations, collaborative brainstorming spaces and lounge-like work and social zones. These planning principles support retaining and recruiting staff and reinforce a safe, secure, healthy and efficient workplace.

5. Design for Social + Environmental Equity

Calls for justice reform and equity will continue to influence the legal system and the court’s role in future decades. Courthouses can ready themselves for this change by programming into the building alternative spaces such as restorative and mediation spaces, problem-solving or specialty courts, behavioral health services, and probation and parole.

With communities demanding more for their tax dollars, courthouse planners should also consider how the building can be used for purposes beyond court-related matters. Embedding spaces for community groups and nonprofits can instill the building with a sense of equity and transparency and help destigmatize negative associations some may have of the courts.

Courthouses of the future must also continue to speak to environmental equity and sustainability. As civic icons, courthouses can be trendsetters, inspiring other new buildings and developments to employ progressive green-building strategies to mitigate climate change and counter local climate challenges. Designers can address this now by practicing an integrated design process and evaluating design decisions through the lenses of sustainability and resilience.

Ultimately, there is no crystal ball that allows us to see into the future. However, by applying the five strategies outlined here, we can be confident that the courthouses we design today have the infrastructure and flexibility to remain in use well into the future.

How long? Perhaps not quite 300 years—like Virginia’s King William County Courthouse—but certainly for a long time to come.

Kristine Bishop Johnson, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP, is a director of HOK’s Justice practice with more than 20 years of experience in the programming, planning and design of justice facilities across the U.S. Have a question for Kristine about courthouse design and planning? Contact her at kristine.johnson@hok.com.