Workforce Phenotyping is a data-informed operational audit of how research teams actually use space—bench work, equipment time, write-up, meetings—translated into a right-sized kit of parts and infrastructure model. Data is reported in aggregate, so it can guide planning decisions without tracking individuals.

For years, the gold standard in corporate research real estate was a universal planning module—a hyper-flexible building where every square foot could support the most intensive scientific needs. The logic was sound: the building could adapt as the science changed.

The problem wasn’t the concept. It was the application. Ultimate flexibility requires universal infrastructure: high-capacity air handling, robust exhaust systems and specialized piping on every floor, regardless of whether the researchers in those zones actually need them. Without a clear picture of who needs what, the safest bet was to build for everything.

Phenotyping changes that calculus. By revealing how scientists actually work, it shows where Super Lab infrastructure is essential—and where simpler, less costly environments will do.

From Job Titles to Observable Behaviors

Traditional lab programming starts with a headcount: How many biologists? How many chemists? But this misses the complexity of today’s research. A scale-up chemist working with fume hoods all day has very different space needs than a computational biologist who rarely touches a bench.

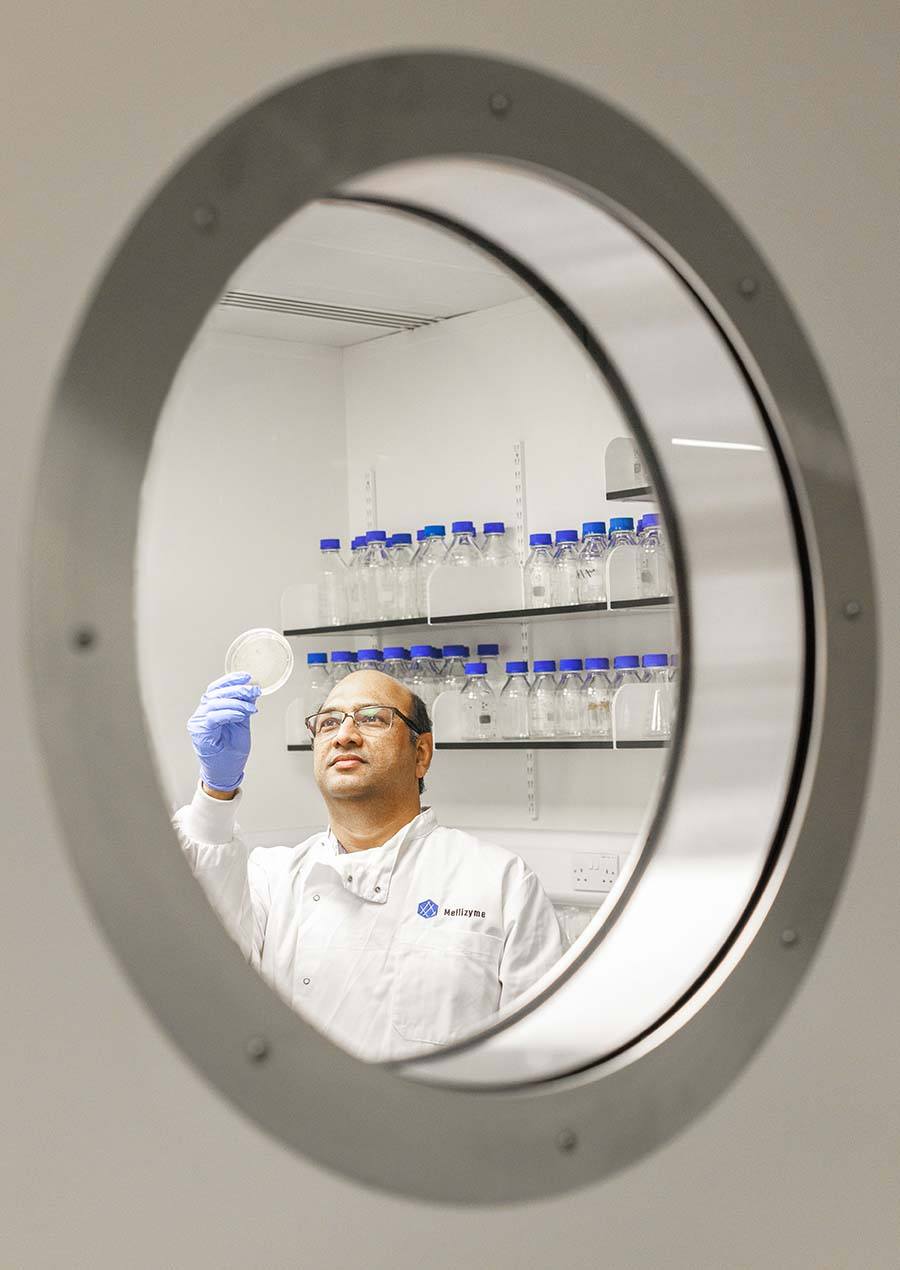

“Instead of asking if they are a biologist or a chemist, we look at the ‘phenotype’ of their daily work,” says Tim O’Connell, HOK’s director of Science + Technology. This approach, developed by HOK’s team several years ago for a project with Stanford Medicine, focuses on observable behaviors rather than job titles.

HOK performs a deep-dive operational audit, measuring work profiles and schedules to calculate ratios of space needed for each group. This allows them to identify the “delta” between a scientist’s desired needs and their actual daily activity.

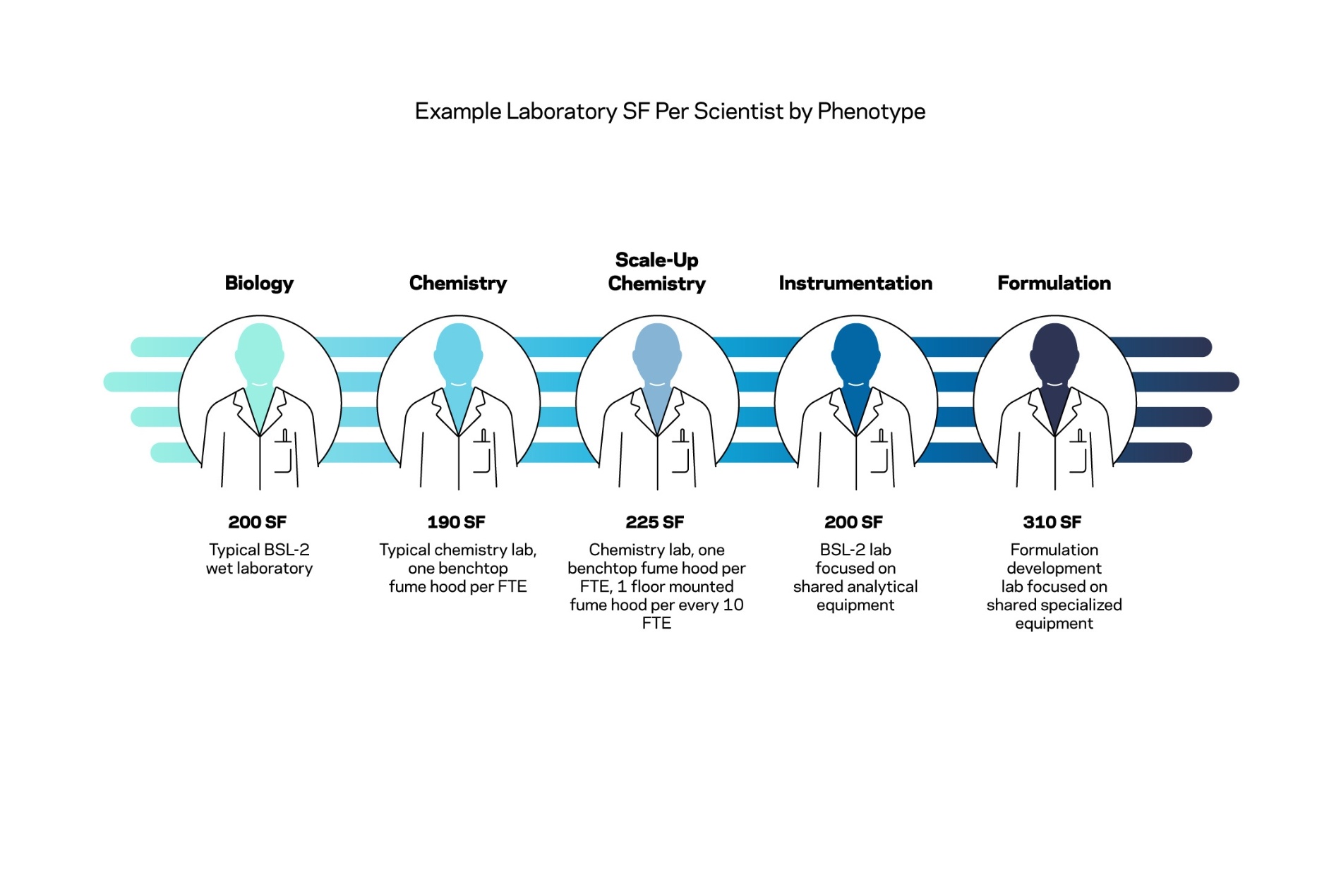

Above: An animated comparison of the different “kits of parts” required by distinct research phenotypes—cycling through chemistry, biology and instrumentation workflows to show how each demands fundamentally different lab infrastructure.

“For lab planners, it means understanding the specific kit of parts each researcher actually uses—including bench space, fume hoods, tissue culture rooms and equipment zones,” O’Connell explains. “By mapping those phenotypes across an organization, we can design infrastructure that flexes where it needs to, not everywhere.”

The math gets specific. Driven by fume hood density and bench configuration, hood-intensive chemistry roles typically require more square footage than most biology roles. Biology leans heavily on tissue culture rooms and cold storage. Instrumentation specialists fall somewhere between, with needs shaped by floor-mounted equipment and vibration sensitivity. Then there’s the growing computational phenotype—researchers who require robust power and data but zero bench space.

The design solution isn’t to create a better box. It’s to understand what people do inside it through Workforce Phenotyping.

The Case for Building Less

Workforce Phenotyping changes the conversation from how much space do we need? to how well are we using what we have?

“We often find that a client’s perceived space shortage is actually a utilization problem,” says Wayne Nickles, Science + Technology practice leader in HOK’s Washington, D.C., studio and a frequent leader of scientific master planning engagements. “By aligning physical space with actual phenotypes, we can unlock capacity that an organization didn’t know they had.”

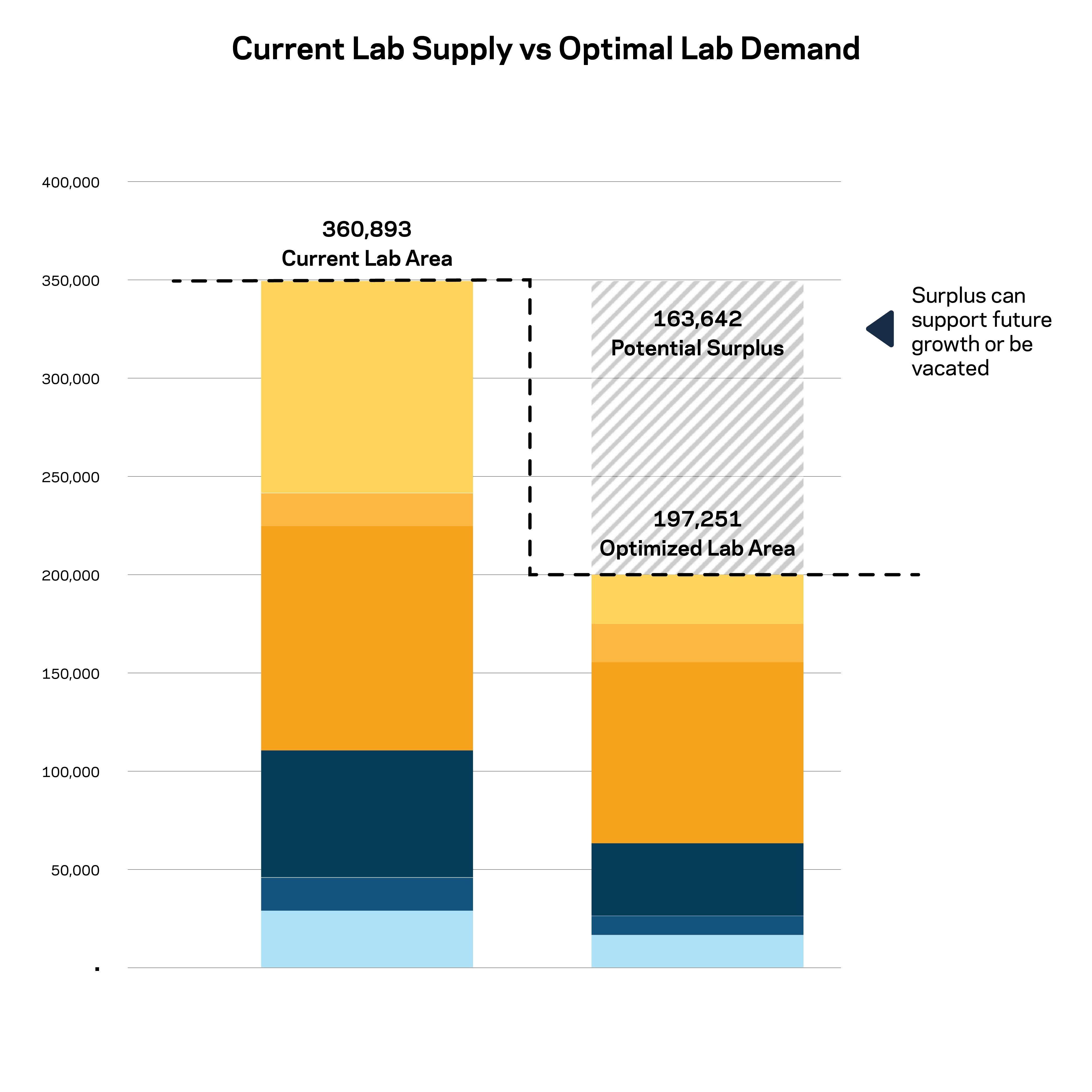

In a study for a global biopharma client, HOK’s team reviewed existing laboratory utilization and found that recently renovated labs were operating at nearly twice the efficiency of legacy spaces. The study identified over 160,000 square feet of untapped capacity at just one campus. This space, unlocked by optimizing the interior footprint of existing building to match actual workforce phenotypes, allows the organization to absorb growth or create swing space for future renovations without the need for breaking ground on a new building.

Using Phenotyping to Right-Size Lab Infrastructure

In a recent project for a major biopharmaceutical R&D site, HOK’s team used phenotyping to quantify how much high-intensity lab space the organization actually needed—and where simpler environments would suffice.

By mapping researcher phenotypes across departments, the analysis revealed that a significant portion of the workforce required robust data and power but minimal bench infrastructure. This allowed the design to allocate fume-hood-intensive chemistry and wet lab space only where the data supported it, rather than defaulting to universal lab infrastructure throughout the building.

The result was a more efficient building that matched infrastructure investment to actual research activity. This reduced costs without compromising scientific capability.

The Lonely Scientist Problem

Once phenotyping clarifies where high-intensity lab infrastructure is really required—and where it isn’t—the next question is how to support the time researchers spend outside the lab.

Efficiency isn’t just about square footage. As research shifts from wet lab work to computational analysis, another problem emerges: isolation.

“Pharma and biotech employees have been in the office four to five days a week since the pandemic,” says Nambi Gardner, a senior workplace consultant in HOK’s Los Angeles office. “And yet they report high levels of isolation. They split time between lab and office, global collaboration has exploded virtual meeting demand, and there’s rarely time to connect. The issue isn’t a lack of amenity spaces—it’s a lack of functional proximity to them.”

In interviews, scientists often estimate that they spend 90% of their time in the lab. Yet surveys put the actual number closer to 40-50%. That leaves meetings, desk work and informal collaboration. Designing exclusively for the lab means underserving half of their day.

To address this, Gardner’s consulting team uses “Day in the Life” exercises, inviting researchers to walk through their typical workday. “It helps us identify the adjacencies that actually matter,” she says. “Where do you grab coffee? When do you need a quiet moment? What will make your day harder or easier? We’re designing for those daily rhythms, not just the science.”

Phenotyping supports this work by revealing the mix of experimentalists and computationalists within teams. With that data, designers can right-size not just lab space but also the adjacent workplace—positioning social and wellness amenities in the natural path between bench and desk.

Softening the Science

The sterile, “white-on-white” lab aesthetic is also changing. Sensory-calibrated environments now better support neurodiversity and well-being.

“We’re introducing elements you might find in a hospitality setting,” says Erika Reuter, a senior project manager in HOK’s New York studio. “This includes things like accent walls, varied finishes and tunable lighting. Providing a variety of settings for researchers to choose from allows everyone to choose spaces where they can thrive.”

This approach reflects a growing recognition that the science community includes a significant neurodiverse population. Recent HOK research found that nearly half of surveyed lab workers identified as neurodivergent. Designing for those with the greatest sensory sensitivity tends to improve the environment for all.

From Programming to Strategic Advisory

Phenotyping shifts the architect’s role. Instead of simply programming square footage for a new building, the work becomes an operational audit—understanding how the business does science and aligning its physical assets to support it.

“This approach builds a unique level of trust,” Nickles says. “We’re showing clients how to unlock the potential of the assets they already have. When you can demonstrate that an optimized renovation yields the same scientific output as a large new capital project, you move beyond the role of a traditional designer and become a strategic advisor to their business.”

And because phenotyping creates a framework rather than a one-time snapshot, it becomes a living operational tool that lets organizations adjust their real estate strategy as their science evolves.

In a capital-constrained environment where talent is scarce and science moves fast, the organizations that thrive won’t necessarily have the biggest labs. They’ll have the clearest understanding of how their people actually work.

Continue the Conversation

To learn more about how these insights can apply to your portfolio, reach out to our team:

Tim O’Connell, Director of Science + Technology, Washington, D.C. | tim.oconnell@hok.com

Wayne Nickles, Science + Technology Practice Leader, Washington, D.C. | wayne.nickles@hok.com

Nambi Gardner, Senior Workplace Consultant, Los Angeles | nambi.gardner@hok.com

Erika Reuter, Senior Project Manager, New York | erika.reuter@hok.com