The COVID-19 pandemic is testing New York City. The viability of the city’s density model, building types and mass transit systems all are in question. Trust in our institutions has been shaken.

Yet a look at recent history should give us confidence that New York City will get up after being knocked to the mat. In the aftermath of 9/11, we rebounded and strengthened building safety and security systems. After Hurricane Sandy in 2012, we began incorporating more climate resilience strategies into our buildings and sites. We adapted and evolved.

What will a post-COVID-19 New York City look like? HOK’s planning, design and sustainability teams are envisioning new ways to make it stronger by doubling down on creating a healthier, more sustainable built environment.

New York is North America’s densest city. Based on metrics like per capita carbon emissions and economic opportunity, cities outperform the suburbs and exurbs. Cities also perform better on important qualitative ingredients of well-being like social connection, arts and culture, and diversity. When we leverage (and enhance) a city’s public transportation system, walkability, and access to parks and places of play, it’s easy to see how cities offer a powerful framework for improving public health.

Some pandemic narratives, however, are challenging the value and safety of both urban density and mass transit. Is New York City down for the count? Or can we design solutions that advance sustainable urban development while boosting the health of our city dwellers? We’re going with the latter.

Here’s a glimpse of a futuristic mixed-use village designed through the filters of HOK’s Architecture of Well-Being:

A Collision of Crises

The coronavirus has given us a fresh appreciation for the tenuousness of our individual and collective health. As often happens with natural or manmade disasters, this pandemic has exposed the vulnerabilities in how we live. We’ve experienced the fragility of our healthcare system and the weak links in our supply chains. We’ve witnessed what happens when people lose trust in the scientific community, government and media. We’ve seen the health effects of food insecurity and poor indoor air quality (IAQ). The systemic inequities that place people from racial and minority ethnic groups at higher risk from the virus have become clear.

Shocks to the system—the type now rocking the world—are common in nature. But our continued well-being depends on our ability to shore up these vulnerabilities and a willingness to face this moment with visionary leadership for post-pandemic change. With an unprecedented collision of health, economic, social and environmental crises fracturing our systems and posing an existential threat, we must act now.

Healthy Individuals = Healthy Cities

HOK is responding to this pandemic by accelerating our commitment to sustainable design to deliver a new “Architecture of Well-Being.”

The tactical responses to the COVID crisis, like installing plexiglass barriers or eating lunch alone will either fade or become part of our daily routines. We want to be more strategic in our response and guide cities like New York toward a healthy, low-carbon and regenerative future.

Six Principles

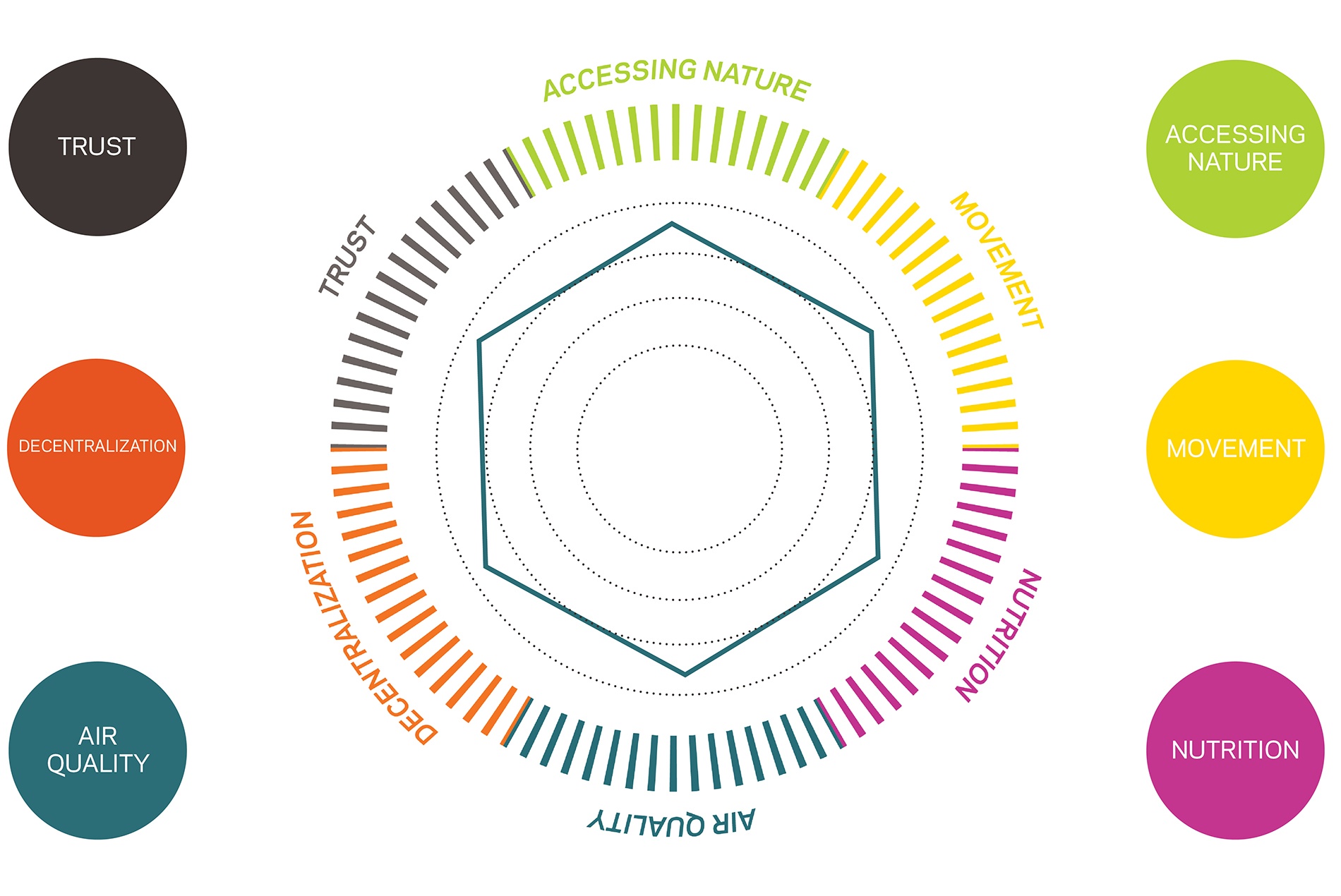

Six fundamental principles drive our integrated design approach for the Architecture of Well-Being: Accessing Nature, Movement, Nutrition, Air Quality, Decentralization and Trust. The principles begin by addressing the health of individuals and then scale up to focus on the health of the city.

When activated by architecture, interior design and urban design, these six principles act as a membrane catalyzing positive feedback loops between individuals and the city. As the rising tide of health lifts all boats, we can reinvent New York City as a model of health and sustainability for the world.

With a design guided by the six fundamental principles of the Architecture of Well-Being, a next-generation life science community could embrace the richness of dense city environments to enhance people’s work-life balance:

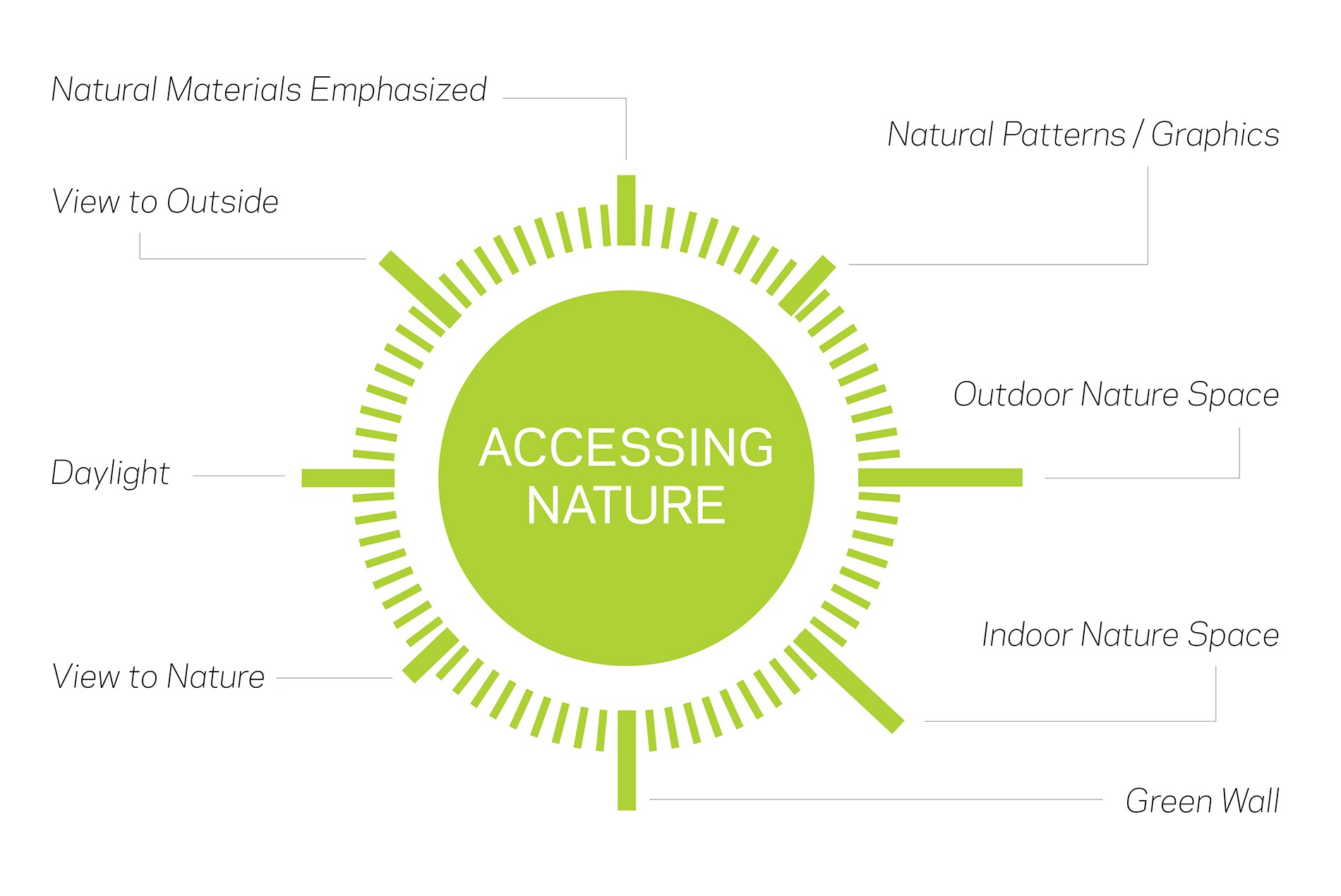

1. Accessing Nature

Humans have an innate need to connect with nature. Whether a person is sitting in the office or walking through Central Park, various studies link exposure to nature to enhanced mental and physical health as well as to better cognitive performance.

For Individuals

We can align biophilic design approaches for buildings with each client’s mission and values. These strategies include:

- Activated outdoor spaces.

- Organic architectural forms.

- Living walls that bring nature into a space.

- Natural materials like wood and stone.

- Daylight and multidirectional views to the outside.

For Cities

Providing access to more green space has positive effects on community cohesion, climate modulation and people’s overall fitness levels. Exposing city dwellers to nature also has an inverse relationship to crime. As nature goes up, crime rates go down.

Strategies include:

- Continue to democratize access to New York City’s waterfront.

- Design more parks that include a wide range of native vegetation to encourage curiosity, engagement, biodiversity and habitat restoration.

- Explore the additive potential of ‘complete streets’ that support safe mobility for all users: drivers, pedestrians, bicyclists and public transportation riders.

- Identify and prioritize viewsheds that allow New Yorkers to enjoy a sense of prospect and refuge.

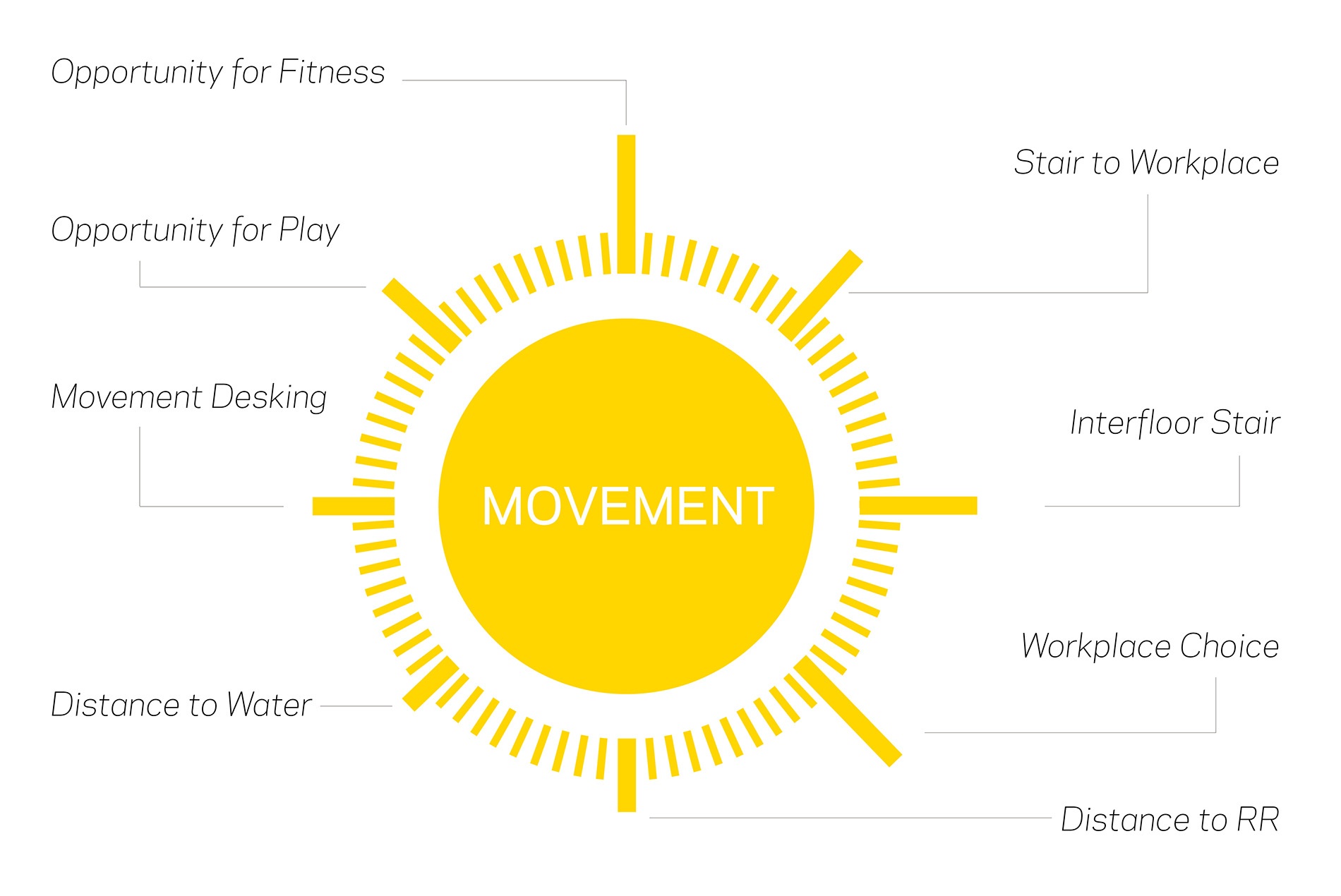

2. Movement

Design interventions that encourage movement throughout the day can help prevent chronic health conditions, strengthening the resilience of individuals and communities.

For Individuals

Is sitting the new smoking? We know that many negative health consequences come from sitting for long periods of time. People with sedentary lifestyles are at higher risk for hypertension, high blood sugar and obesity. These same conditions often are associated with poor outcomes for COVID-19 patients.

To eliminate barriers for movement in the workplace, we leverage active design elements. Strategies include:

- ‘Irresistible stairs’ are prominent, intuitive and brought to life by daylight and views. Making them wider accommodates physical distancing and fosters spontaneous chance encounters between knowledge workers.

- Providing people with plenty of workplace choices frees them to move to different locations throughout the day.

- Alternative desking options like sit-to-stand desks or walking pads encourage motion.

For Cities

Strategies include:

- Redesigning existing rights-of-way to better accommodate all modes of travel, reprioritizing them based on the social benefits of each. A model to determine the priority assigned to each mode would factor in:

- Impact on individual health

- Potential burden to the healthcare system

- Basic economic activity

- Route efficiency

- Load capacity

- Social distancing ability

- As demand for conventional parking shrinks and the city replaces on-street parking with cycle tracks or protected bike lanes, we can leverage ‘road diets’ to slow down vehicles and prevent accidents.

- Electric bus rapid transit systems with separate express and local lanes along with autonomous medium-capacity public transport can reduce New York City’s carbon footprint.

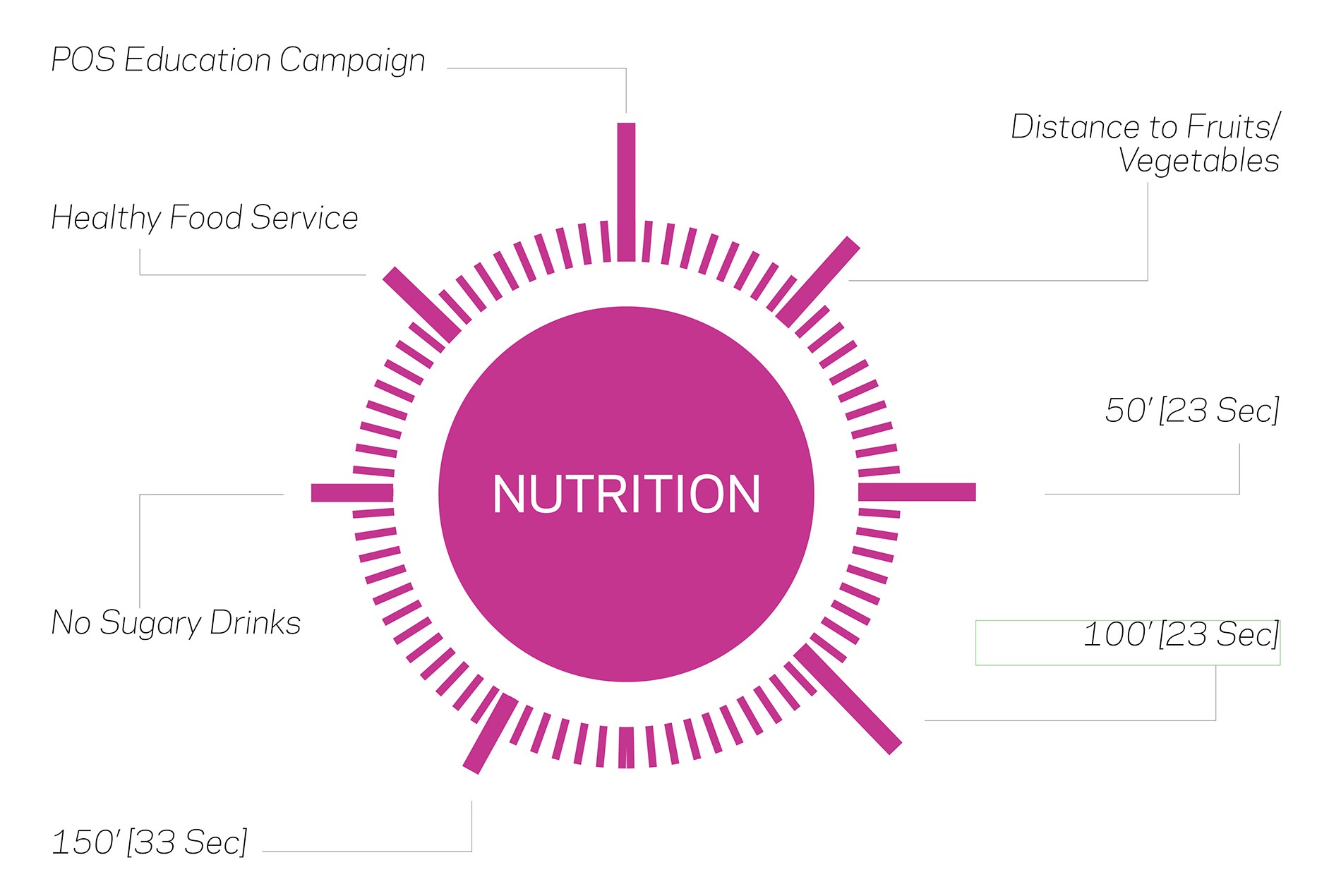

3. Nutrition

There are direct positive connections between nutrition, health and cognitive functioning.

For Individuals

Obstacles to increased consumption of fruits and vegetables include cost, availability, convenience and social norms. The workplace provides many opportunities to overcome these barriers.

Strategies include:

- Common areas like kitchenettes and cafés can offer free fruits and vegetables using touchless technology, pre-ordering and daily reminders.

- Educational signage at points of choice can encourage healthier food, snack and beverage options.

- Organizations can establish nutrition standards that prioritize nutrition and eliminate or reduce trans fats, artificial ingredients, refined ingredients, preservatives, and extra salt and sugar.

- Organizations can replace beverage vending with touchless water stations that offer naturally flavored waters.

- Organizations can encourage healthy diet choices by providing incentives like cash payments, recognition programs or employee competitions.

For Cities

Strategies include:

- We can help eradicate food deserts by incorporating urban farms that produce low-cost or free produce for adjacent communities.

- We can design multifunctional green spaces with both park and urban farming infrastructure.

- New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene can incentivize productive rooftop gardens through an upstream expansion of the current New York farmer’s market SNAP/Health Bucks program.

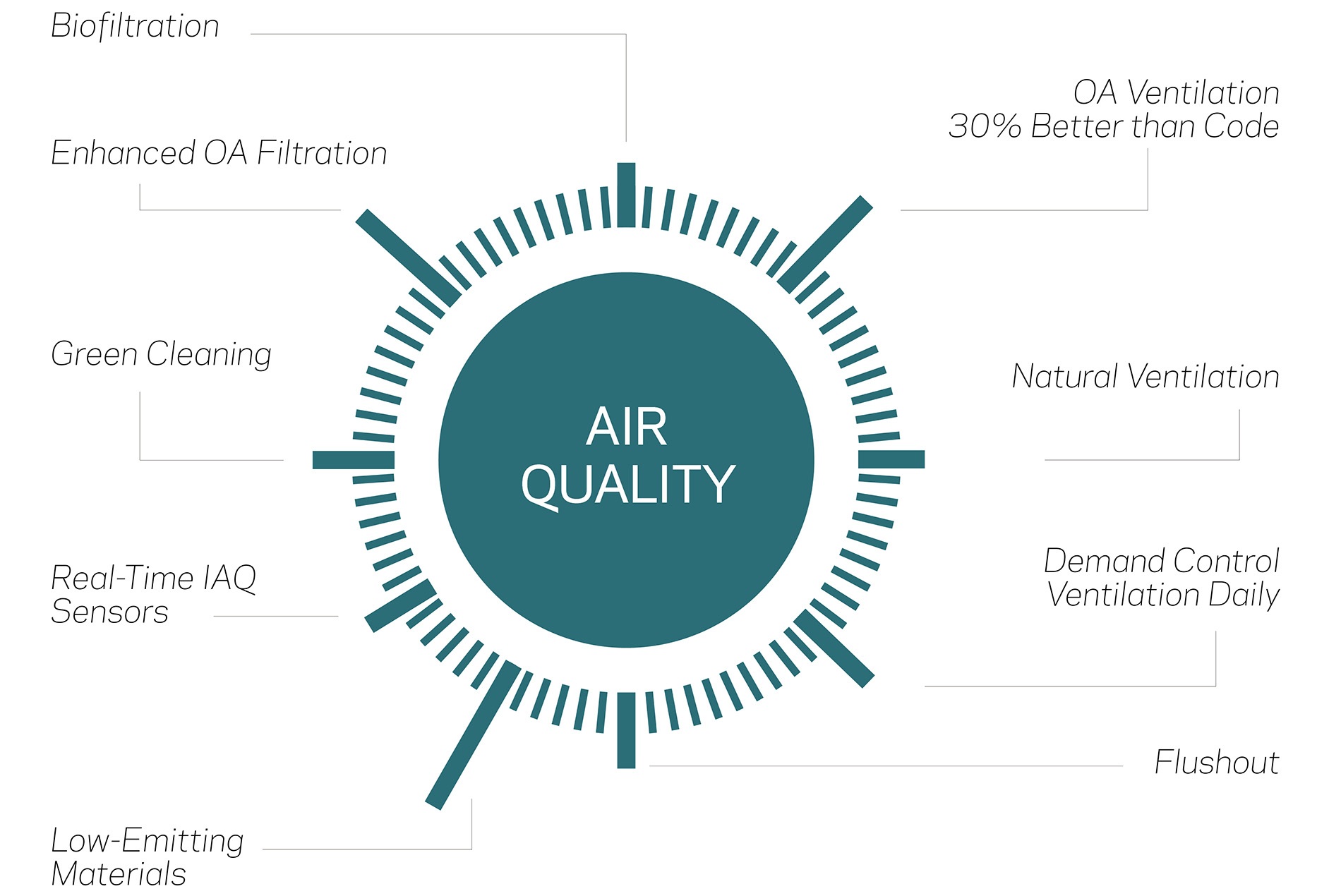

4. Air Quality

In the Take Care New York 2020: Community Health Priorities initiative, half the communities surveyed listed air quality as their top health concern.

For Individuals

A recent Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health study called poor ambient air quality a more significant contributor to the COVID-19 death rate than preexisting medical conditions, socioeconomic status or access to healthcare.

Many of the actions we can take to boost IAQ center around HVAC systems. We can explore:

- How much outside air is provided above code minimum? What is the optimum balance of filtration and energy use? Can we flush the space?

- Are we considering operable facades that allow for natural ventilation?

- How smart are the systems? Are they equipped to quickly react to changing conditions? Can the systems be compartmentalized?

- How clean are the systems? Is the air being delivered picking up new contaminants in the ductwork?

Other strategies for interior environments include:

- Select plant species for biofiltration performance and add other biophilic elements to the space.

- Specify the lowest-emitting building materials and furniture.

- Equip stakeholders with all the tools needed for robust green cleaning programs.

For Cities

The continued acceleration of three major trends can improve ambient air quality. Strategies include:

- The electrification of vehicles.

- A boiler conversion blitz that moves older building stock away from oil toward biofuel or full electrification.

- Enhanced air pollution removal from power plants and major industrial facilities.

5. Decentralization

Resilient systems are inherently decentralized. If one component fails, the system can repair itself and continue to thrive. This is true across the spectrum: from forests, to power plants, to organizations and cities.

For Individuals

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the distribution of teams across decentralized workspaces. This is the future of work. It offers more flexibility and work-life balance, opportunities for healthier methods of commuting, real estate savings and improved business continuity for organizations. It will create economic resilience needed to withstand the next crisis.

The pandemic also has fast-tracked positive trends like paperless work, non-assigned workstations and providing occupants with more choices about how and where to work.

For Cities

In contrast to a single central business district punctuated by a cluster or two of skyscrapers, a decentralized city will have several geographically dispersed CBDs. Pushing economic opportunities deeper into the boroughs will elevate equity, health and sustainability in a more polycentric New York.

Strategies include:

- The combined effect of geographic distribution and hybrid remote/in-person work schedules can relieve peak-load stress on New York City’s public transportation system while allowing for physical distancing.

- A redesign of existing rights-of-way to prioritize modes of travel with the highest social benefit will distribute travelers along an array of modes instead of bottlenecking them into a single mode of public transportation.

6. Trust

The pandemic has accelerated an erosion of trust in society’s institutions, the scientific community and the media. But trust is the glue that binds societies. Without it, we’re more vulnerable to future disasters.

Combining accurate and real-time building performance data with new levels of transparency will help building owners and managers regain the trust of their occupants.

Likewise, giving city residents access to accurate, verifiable data will help rebuild their trust. Based on the positive public reaction to Governor Cuomo’s data-driven reopening strategy, the phrase “in data we trust” has the potential to establish a permanent place in the psyche of New Yorkers.

For Individuals

Strategies include:

- Regular IAQ testing results can be provided to all occupants. The data can inform their actions about where to work throughout the day—or whether they should even work in that building.

- Data transparency enables organizations to turn liabilities into assets by immediately addressing problems to build trust.

- Joint ownership of issues and an open dialogue between individuals and organizations are critical for rebuilding trust. Transparency regarding the frequent cleaning and maintenance of buildings, including any natural features, is important—as are unobtrusive health screenings, visible handwashing stations and paid sick leave.

For Cities

Concepts related to trust can scale to the neighborhood and city. Strategies include:

- Ambient air quality data can inform daily activities and expedite corrective actions. This data can inform policy decisions and precise allocation of resources to alleviate environmental and health issues that are prevalent in Environmental Justice areas.

- Regular maintenance of places where frequent social contact takes place. This includes public transportation, parks and green spaces, and assembly spaces. Small actions can have a big impact.

A Day in the Life

What would it be like to live in one of the healthy vertical communities we propose? Imagine:

Well-Being Performance Feedback Tool

Implementing HOK’s Architecture of Well-Being in projects requires measurement, feedback and continuous improvement.

The six interoperable principles—Accessing Nature, Movement, Nutrition, Air Quality, Decentralization and Trust—form a framework for achieving the balance currently missing from the built environment.

The framework is flexible. Understanding there will never be a one-size- fits-all solution for New York City, we have created a menu of design actions supporting each principle. Designers can select the strategies that work the best for each project and recommend new ones.

Our Well-Being Performance Feedback tool balances this flexibility with a holistic approach. The six principles are divided evenly and add up to a total score of 100. A project that earns a score of 100 or higher has achieved the Architecture of Well-Being.

Parametric design tools will allow teams to incorporate feedback early in design, in near real-time, and to continuously test ideas for improving the framework.

For a more detailed look at The Architecture of Well-Being, check out the Mixed-Use Case Study and Science + Technology Case Study.

HOK contributors to this study included Max Driscoll, Ken Drucker, Blanca Dasi Espuig, Phillip Gangan, William Kenworthey, Jeremy Kramer, Aman Krishan and James Mallory.